|

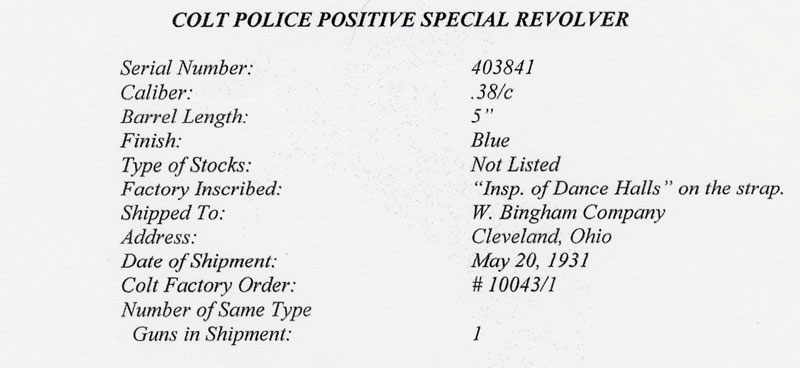

Early Colt Police Positive Serial Number 403841 with 5"

barrel - Factory inscribed "Inspector Dance Halls" with

blue finish and medallion checkered walnut grips. This

Police Positive was a single gun shipment to W. Bingham

Company on May 20, 1931. It was processed on Colt

Factory Order number 10043/1. Letter confirms factory

inscription "Insp. of Dance Halls" on the strap.

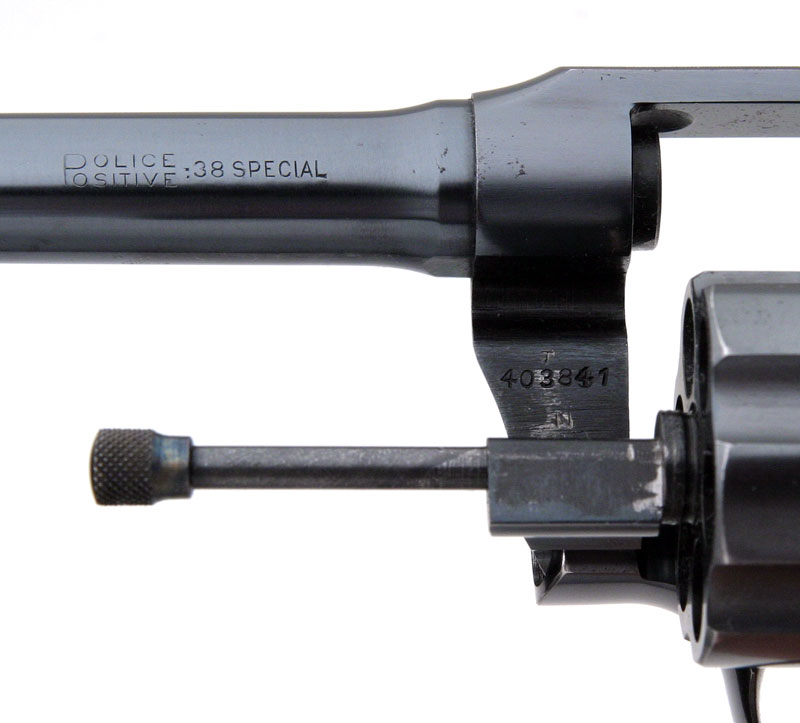

Left side of barrel marked:

| P |

olice

ositive |

-.38 SPECIAL |

Colt Police Positive .38 Special - factory inscribed

"Inspector Dance Halls" on the rear grip strap.

Marked on top of barrel:COLT'S PT. F.

A. MFG. CO. HARTFORD. CT. U.S.A.

PAT'D. AUG. 5, 1884, JULY 4, 1905, OCT. 5, 1926

Police Positive .38 Factory Inscribed serial number

403841

with 5" barrel - right side. Revolver is fitted with

Colt factory flush medallion checkered walnut grips. Front

site is standard early rounded type.

Close-up photo of the checkered trigger (Colt refers to this

as a "checked trigger.")

Top view of hammer, frame and barrel.

Close-up of top of frame.

View of the rear of the hammer and frame.

DANCE HALLS - The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

DANCE HALLS. During much of the 20th century, social dancing

was one of the major recreational activities in industrial

cities such as Cleveland. During the peak years between the

1920s and the 1950s, there were over 150 dance halls

accessible to Greater Clevelanders, not including several

hundred more dance floors in HOTELS, nightclubs, and private

halls. These included facilities extending to Conneaut Lake

Park, PA, in the east; Meyers Lake Park, Canton, in the

south; and Cedar Pt. Park, Sandusky, in the west. Although

cities such as New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles had larger

facilities, Cleveland became well known to musicians and

bandleaders as a place to develop with a chance to move into

a position of national prominence. One of the earliest

social dances in Cleveland was held at Ballow's Hall in

1854. Dances at that time included the two-step, the waltz,

and later the cakewalk and other syncopated steps. By 1910

popular sheet music started to appear with parts for

dance-band instrumentation, and by that time dancing became

viewed as an adjunct to other activities such as swimming

and sports; several dance pavilions were built at parks

built in the early 1900s. At EDGEWATER PARK, a dance

pavilion overlooked a bath house on the beach below. GORDON

PARK had a dance area in conjunction with a large bath house

extending over the lake near E. 72nd St., and a park

building at Brookside, off Fulton and Denison Ave., included

a dance area on the 2nd floor. Another city pavilion was

located at Woodland Hills Park, at Kinsman and Woodland

avenues. The city pavilions were out of existence by the

mid-1920s. Private AMUSEMENT PARKS opened at this time also

offered dancing, in addition to a variety of other

activities suited to families and group outings. Those with

dance floors included White City at E. 140th and Lakeshore;

LUNA PARK, where the dance pavilion was of generous size,

with the dance floor at ground level; EUCLID BEACH PARK,

which had one of the finest dance floors in the region and

which for a time offered outdoor dancing; and PURITAS

SPRINGS PARK, which had a plain ballroom and also featured

an outdoor dance area.

The society dance craze, influenced by the popularity of

Irene and Vernon Castle, led during the World War I period

to a changing social pattern. Before this time, dance halls

were not always considered proper places for members of

polite society; therefore, dances were generally private

functions. Some of the more affluent and prominent citizens

built their homes with a ballroom and party facility,

generally on the 3rd floor, with access by special stairs or

elevator. On the lower end of the social scale, saloons

offered some dancing. Saloon dance floors disappeared after

the 18th Amendment, the Volstead Act, took effect in 1920.

They were replaced during Prohibition by supper clubs with a

more, sophisticated atmosphere that reflected the influence

of society dancing. Some places violated the Volstead Act

while maintaining an atmosphere of prohibition. Most hotels

countrywide included ballrooms or party rooms to provide for

dancing as well as other group activities. Many local hotels

created their own special clubs, with guests of the hotel as

potential clientele. Radio broadcasts originated from hotel

supper clubs on a regular basis during the 1930s and 1940s,

with some broadcasts carried on a national network,

publicizing both the orchestra and the hotel. Numerous

private clubs and fraternal organizations provided a hall in

their building suitable for dances as well as other

organizational functions.

With the increased popularity of dancing in the 1910s and

1920s, many localities enacted laws to regulate conduct in

the dance halls, which were viewed by some citizens as

potential havens for moral laxness between the sexes. By

1930 28 states and 60 large cities had adopted laws or

ordinances to regulate public dancing; Cleveland developed

Ordinance 690, defining regulations for dance places and

dancers. Public Dance Hall meant any academy, room, place,

restaurant, or nightclub where dancing was held, or any

room, place, hall, or academy in which classes in dancing

were held or instruction in dancing was given for a fee. The

ordinance included restrictions on intoxicating liquor and

gambling and required decorum of behavior and dress. Smoking

was restricted to designated rooms. Dance hall inspectors

were first hired by the city in 1929 to check places covered

by the ordinance. By 1930 there were nearly 150 dance-hall

inspectors covering the city. Dance halls also had an

employee assigned to check decorum and dress. Dancing too

close or cheek to cheek was discouraged. After a marathon

dance contest held at the Old Taylor Bowl, at E. 36th St.

and Harvard, the city ordinance was amended to prohibit such

activities. Dance-hall activity in Cleveland reached a peak

during the Big Band era of the 1930s and 1940s. Many of the

major ensembles of that era, including those of Glenn Miller

and Tommy Dorsey, played at locations in the Greater

Cleveland area. However, interest in ballroom dancing

declined through the 1950s as musical tastes changed, and

other forms of entertainment such as TELEVISION became

available. Ballroom and club owners experienced a rise in

operating expenses and increased fees for bands. That, along

with diminishing attendance, especially in some urban areas

where social unrest brought a few roving gangs to disrupt

dances, forced many operations to close or cut back their

schedules. Owners changed their halls from dancing to party

centers, roller rinks, bowling lanes, or a variety of

commercial enterprises.

Although some dance halls existed during the 1800s, most of

Greater Cleveland's most prominent, non-park facilities were

built between 1900-30. The ARAGON, 3179 W. 25th St., was the

last surviving ballroom within Cleveland, until it finally

expired in 1993. It was originally built in 1919 as the

Olympic Winter Garden, catering to dances, roller skating,

banquets, weddings, and prizefights; ownership changed in

1930, and the name became Shadyside Gardens. Several years

later, after remodeling, the ballroom was renamed the

Aragon, after one of Chicago's finest ballrooms. The Crystal

Slipper, 9810 Euclid Ave., opened in 1924 as the largest and

finest of the city ballrooms. Within several years the name

was changed to the Trianon, after another famous ballroom in

Chicago. This dance floor could accommodate 4,000 persons.

Dances were held nightly, and popular name bands were

featured for a night or short-term engagement. During the

early 1940s, the Trianon, under new ownership, became the

Trianon Bowling Lanes, which operated through the 1950s,

when the property was acquired by the CLEVELAND CLINIC

FOUNDATION; the building was razed to become a parking area.

Danceland, 9001 Euclid Ave., operated as a dance hall with

summer roof garden through the 1920s and 1930s, when, under

new ownership, it was converted to a roller rink and renamed

Skateland. By the 1960s, new owners converted and remodeled

the building for commercial use as a food store and other

shops.

The Ritz, 3705 Euclid Ave., was active as a roller rink

through the 1930s, with the name changing to the Greystone

and later to the Marcane, until the structure was given over

to commercial use in the 1950s. Later the entire block,

including the Cleveland Arena, was demolished. Bedford

Glens, located off Glen Rd. in BEDFORD, began as a park in

the early 1900s; soon a barnlike structure was built, and it

became a year-round dance and bowling resort. Although the

ballroom was successful, a fire closed it in 1944.

SPRINGVALE BALLROOM AND COUNTRY CLUB, 5871 Canterbury Rd.,

NORTH OLMSTED, was still operating in the 1990s. It was

built in 1923 by the Biddulph family, who managed it

throughout its history. This ballroom was remodeled on at

least 2 occasions, and in the 1990s dances were held four

nights a week. Only a few dance halls continued to operate

in the 1990s, and these averaged fewer than 2 nights of

dances per week. Hotels, clubs, and fraternal organizations

continued to hold special dances: one restaurant, Swingos at

the Statler, regularly scheduled Sunday brunches with

dancing, capitalizing on a revival of interest in Big Band

music during the 1980s. However, despite predictions of a

revival of ballroom dancing and music, such activities

continued only at a minor level in the 1990s when compared

to their peak period of popularity during the 1930s and

1940s.

Robert Strasmyer |